In my writing, I switch back and forth between sharing about my own personal experiences and general discussion of harmful churches and religious trauma. I’ve done my best to clearly communicate when I am speaking specifically about my own experiences in a specific community. All else is general discussion relative to certain types of church environments and the patterns often present in those spaces.

Even though it has felt very important for me to share my story, I’m a teacher by nature. As such, it was only natural for me to share my story alongside information and contextual framing that – for me personally – has been helpful in processing and understanding not only my own experiences, but also the sadly numerous experiences of religious trauma many others have had.

After the initial shock and disorientation of what happened between me and our lead pastor subsided, and after months of trying to figure out how to be honestly humble and hold my own in a very messy situation, I finally started to fight back against the idea that I’d done something “wrong.” Eventually, that pastor and I were able to agree on the word “mistake.” Though, to be honest, I’m not sure I’d agree to that word now. Not that it matters. I agreed then, and, perhaps more importantly, so did he. I had misjudged a friend’s receptivity in a conversation, and that was the starting point of what has become one of the most important mile markers in the story of my life.

To clarify, the “mistake” I made was that I shared – very passionately – with a friend about some of my frustrations with, critiques of, and concerns about the church we both attended. I’d also shared about the lead pastor’s inaction in some areas of concern that I’d discussed with him on a number of occasions. I later learned that I shared these things in a way that felt unsettling to my friend. My supposed “mistake” was not knowing that was how she was feeling as I shared. Eventually, she felt compelled to share something of the conversation with our lead pastor. And though I feel no lingering bitterness or anger toward her (it’s not that hard to empathize with someone who, just as I did, made choices to prioritize the security of a system above other things she valued), in the scope of my life and the life of my family, the aftermath was cataclysmic.

"In the culture of that church, it seemed to me that sharing anything less than positive about another person was readily branded as ‘gossip,‘ …the problem is that the definition of ‘gossip’ was all wrong.”

Once I knew that the pastor had been made aware of that conversation, I understood immediately that it would be a problem. A big one. In the culture of that church, it seemed to me that sharing anything less than positive about another person was readily branded as “gossip,” and gossip was something often warned against. Were there Sunday messages focused on the evils of gossip? No – at least not that I recall. But, for me, the social pressure and implicit agreement within this community upholding the idea that gossip was a serious infraction was very real. The problem is that the definition of “gossip” was all wrong.

To speak about my own feelings, experiences, thoughts, and ideas is NOT gossip. To speak purposefully, albeit critically, of someone else – whether a leader, a spouse, or otherwise – is not gossip. That’s just genuine sharing.

My big picture concerns, most of which centered on the way women were oriented and positioned within the church, were never centered on dispute or conflict. I was doing what I’d been told was part of my role: I was helping collaborate and “lead together.”

I raised those concerns many times through the years in individual meetings that I initiated with the lead pastor. In those meetings, I felt that my collaboration and perspective were welcome and valued. Only over time did I notice that no matter how often and how “helpfully” I spoke up, nothing really seemed to change. In our meetings, the pastor always left me feeling heard and thinking he was interested in responding to my feedback with action. Yet, that meaningful action failed to materialize. For years.

Once I knew that my pastor was aware of the conversation I had with my friend, I got on the phone with him. I was supposed to preach at the youth group that night; the regular teaching leader was on extended leave, and I was taking her place for the duration. The pastor was also scheduled to be there helping that night. He asked how I thought we should handle the situation presented by that night’s schedule.

I said we were both grown ups, and that, although there was stuff we needed to work out, I thought we could just go, be in the room together, and act as normally as possible. His response was something that shocked me then, and speaks volumes to me now.

He said something like, “You’re acting like this [situation] is a 2. But to me, it’s a 10.” He went on to tell me that he didn’t feel comfortable or safe having me in the room that night, and that he’d just figure out the teaching himself. I was not permitted to attend.

"Regardless of the why, a failure to ask questions eventually becomes tacit permission for the unexplained events to continue, regardless of their nature."

I never did find out what he said that night about where I was. Aside from one friend, whose daughter eventually asked her what had happened with me, there was never anyone who, to my knowledge, asked any questions. At all. Not-asking seems to have been deeply ingrained into the culture of the church; this could very easily be linked to the pervasive condemnation of “gossip.” Regardless of the why, a failure to ask questions eventually becomes tacit permission for the unexplained events to continue, regardless of their nature.

It’s not that I think anyone at that church wanted me to be hurt, or would have liked that I was, had they known. Yet, when I very suddenly stopped leading in the other visible ways I had been, still not one person asked me what was going on. None of the people I led and taught next to asked a thing. And after I shared a few vague and evasive things with my closest friends, no one asked for more. No one said, “That doesn’t really add up.” No one. And I, of course, didn’t offer.

A day or two after being told to stay home from that first youth group night, I was astonished to find out that, though the pastor had pronounced what was happening “a 10,” he didn’t even yet know what I’d said. As I came to understand it, all he’d been told was that I had said something [critical] about him and that there needed to be some follow up. I don’t know, but suspect, that my friend’s discomfort with what I’d shared was probably also communicated to him.

A time was scheduled for the three of us to meet, and at what was essentially the start of the conversation, the pastor looked at me and said, “So, what’d you say?”

I told him. Everything I remembered.

After a beat, he looked at my friend and said, “Is that it?” But it didn’t sound to me like he was testing to see if I was holding back; what I heard in his voice was surprise. I always thought that was because he’d already heard it all before. Multiple times. From me.

Nevertheless, on top of preventing me from teaching at the youth group that first night, his next steps were swift, absolute, and surprising. At least, at the time, I was surprised. Now, I see it differently. In that first face-to-face meeting, I was stripped of all my teaching and leading responsibilities, which were many. The only exception was that I was permitted to continue co-leading a small group that met in a friend’s home.

I’d been consistently helping to lead parts of Sunday morning services, even delivering the sermon a couple of times. I was teaching newcomer’s classes, had developed and taught a series of lessons for our small group leader meetings, and was serving and leading in many other capacities, including the Youth Group preaching I mentioned. I did all of these things as a volunteer, without any kind of compensation. My punishment (I don’t know what else to call it) was effective immediately, and had no foreseeable end in sight. Later, I was told I might be able to earn back trust over time. I marvel at that now.

These consequences were, to the best of my knowledge, unilaterally imposed by one man whose responsibilities for the care and tending of an entire community (which included me) seemed, in my opinion, to take an abrupt backseat to his desire to protect his own reputation and the culture of untouchability that had, in my view, been built around him.

I am so thankful, looking back to these events, that I had people around me who tried to persuade me from the beginning that I hadn’t done anything wrong. I was in a state of panic. For reasons I couldn’t then understand, it felt like a VERY VERY big problem to have the lead pastor at all unhappy with me. These friends of mine, looking at the situation from the outside, were beacons of truth for me; the clarity of their outrage and anger was something I couldn’t fully understand at that point. I was deeply indoctrinated and aligned with the cultural expectations of that church, and so I simply couldn’t really see how my “infraction” was anything other than exactly that.

I’m so thankful now that those friends and loved ones persistently expressed their anger at the injustice of what was done to me, and challenged the appropriateness of the dynamics in play, because I could not do so at the time.

But it’s been five years. And I can do so now.

"The cost of belonging in that community always felt so high. And even someone who tried to pay it again and again and again, I was always left feeling that I was somehow on the outside."

At one point early in those aftermath talks, the pastor told me, “I just don’t feel like you’ve got my back.”

I find myself smiling ruefully as I type out that sentence. It speaks volumes to me now. In so many ways, it sums up the harmful underpinnings of the relationship I had to that man and to that church. The cost of belonging in that community always felt so high. And even someone who tried to pay it again and again and again, I was always left feeling that I was somehow on the outside. My experience told me that one of the key unspoken rules for belonging in that community was a commitment to protecting the perfect image of the church, its members, and especially the man who stood in power at its center.

In nearly every church, there are people who hold power, and structures that reinforce their control of that power. (In healthy spaces, churches work to actively engage with that reality and intentionally undermine it, so that power can be dispersed and continually decentralized.) But powerful leaders aren’t the only concern. It’s also important to note that pastors who, instead of caring for and pastoring their congregants, act in abusive ways would not have a place to do that damage without a church whose culture permitted their abuses of power. Together, those things are the “system” that is protected by things like intense condemnations of what’s inappropriately branded as “gossip,” and people who may wonder at what’s gone on behind the scenes, but consistently choose not to ask too many questions.

Long before this whole episode went down, I was a part of regular meetings for the leaders of the church’s small groups. These meetings often included encouragement and direction for the small group leaders to do a better job of pastoring the individual people in their small groups. After one meeting, I asked the lead pastor a question that, in my opinion, was emblematic of the frustrations many of the small group leaders had been expressing for years. I asked, “but who is pastoring us, [the small group leaders]?”

It seemed to me that my question caught him off guard; he said, “Well, if you guys have something going on, I sure hope you’d tell us.”

In my own experience, that was pretty much the extent of the engagement with personal difficulty I could expect from that pastor. And don’t worry; I knew it. I never asked for more.

"I don’t regret the love I invested into the many wonderful relationships I had while there, though an overwhelming majority of them were unable to survive my family’s exit from the church."

In retrospect, my heart twinges a bit thinking of all the time, money, energy, and heart I poured into that church and its plans. I don’t regret the love I invested into the many wonderful relationships I had while there, though an overwhelming majority of them were unable to survive my family’s exit from the church. The structure and dynamics of the place don’t seem to leave a lot of room for those who leave to really stay connected to the people who’d been promised to them as friends and “family” for life.

Like so many things, for me and for my family, it seems that those promises of devotion and friendship were contingent on some pretty costly conditions. As it played out, it seems to me that I was permitted critique and concern, but shared only in one-on-one private conversations with the pastor himself. In my view, the statement I shared above explains a lot: he didn’t feel like I had his back. Because, somehow, apparently, I was supposed to put the protection of that pastor’s reputation and the church itself above many other important things – including my own desire to use my voice and share my concerns with a friend? At the time, that was a view I’d leaned into unquestioningly. Did anyone ever tell me that explicitly? No, but I knew.

When we finally left, nearly four months after that initial conversation in which I was told I couldn’t come to teach that night, I was so confused. I was asking, “What the heck just happened?” I’d sincerely thought we’d be a part of that community forever. We even tried, in those intervening months, to figure out how to stay. I feel so sad for myself now as I type those words. We really did; even after all that, my family and I tried to stay.

I was still deeply enmeshed in a framework that told me that I had been the real problem, and I didn’t want to lose the many dear friendships I’d made and nurtured. It was the only church my kids had ever known, the center of our social lives, and the hub for most of our relationships. There was a lot of loss on the line.

I’d be lying if I didn’t admit to feeling disappointed when I think now about the people I know who’ve stayed, even as they have known or observed problematic behavior like that shared in the stories gathered here. But I also feel compassion. I can speak from experience. Walking away from this church cost us what felt like our whole world, and the loss some may fear if they contemplate disconnecting from this church is real. It could be very, very painful. It was for me. Yet, in so many ways, and on so many levels, I am profoundly grateful we aren’t there anymore. The time period around these events has been one of the most significant and most agonizing disruptions of my life and yet, I wouldn’t go back for anything. Even though it felt brutal, I’m glad any continued hopes I may have had for “changing things from the inside” (because that’s exactly what I had tried to do – for far too long) were outweighed by the events that prompted us to go.

I’ve had a lot of time to process those events and the months surrounding them, including the aftermath for myself and my family. I’ve had lots of healthy support in contemplating the various angles of the situation, and I’ve spent a lot of time in the intervening years learning about the dynamics of spiritual and church abuse. Removed from that environment, unattached to the influence and power exercised by that pastor, and much more informed, I now see the situation through very different eyes.

It took me a long time to name some of the problematic elements in what was said and done, but now that I’ve learned what I have and heard the stories I have, what once felt like a tidal wave of disorientation and confusion seems clearer.

I had objections to the ways the pastor talked about women and the roles of women. I objected to the ways that, under his leadership, women were positioned within the culture of the church and, by extension, the homes of its members. My honest belief was that these things came out of a lack of awareness and sensitivity, rather than an intentional misogyny or conscious strategy. I was trying to help address what I naively saw then as an understandable oversight. But honest and sincere critiques – almost all of which I’d shared with him many times in private meetings – seemed suddenly to be responded to as if they were something much more malicious once he became aware that I’d shared them with someone else.

That dynamic is an interesting one in any context. Why might it be okay for someone to have critiques, as long as they’re shared in a contained way? What about making a critique more widely known transforms it into a problem? What’s the essential difference between those two scenarios? Who benefits when critique is kept from public awareness? And why is the response to one so very different from the response to the other? In truth, I may not have asked those questions at all had I not been on the receiving end of the blowback. Unfortunately.

Somewhere along the way, I’d absorbed the idea that Mathew 18 was a solid foundation for the view that I’d done something “wrong” simply by sharing my concerns. The passage reads like this:

“If your brother or sister sins, go and point out their fault, just between the two of you. If they listen to you, you have won them over. But if they will not listen, take one or two others along, so that ‘every matter may be established by the testimony of two or three witnesses.’ If they still refuse to listen, tell it to the church; and if they refuse to listen even to the church, treat them as you would a pagan or a tax collector.” (Matthew 18:15-17)

Yet, the situation I experienced wouldn’t have been an appropriate application of Matthew 18. First of all, it says “if your brother or sister sins.” As I’ve already said, I wasn’t addressing sin. Neither criticisms nor conflict are inherently sinful. Though I would take a more nuanced view of this now, I believed I was simply addressing a blindspot.

Secondly, I’d brought up my concerns directly many times. And if action can be considered a mark of “listening,” I wasn’t listened to. So, even if I wanted to take a principle described for use in a very different culture 2000 years ago and apply it literally and exactly today as if it were an exhaustive guideline for modern church life (which, in general, I would not recommend…misapplication of this passage is implicated in many more egregious harms than those in my own story), it still states that sharing my concerns with others was the next Biblically indicated step.

You’ll also notice that, in Matthew 18, the subsequent prescribed step is to share about the sin in question with “the church.” That word, in its original Greek, means “public gathering” or “congregation.” That’s a call for a public address of whatever sin is at hand.

"…I know there are many churches who use this principle from Matthew 18 as a foundation for what amounts to secrecy and a lack of transparency. And frankly, as a well-studied reader of my Bible, I’d like to point out that that’s a gross misinterpretation of the text at best and, at worst, an intentional obfuscation and manipulation of the principles presented in this scripture."

I’m sharing this piece about Matthew 18 not because I feel any need to defend my “mistake” or whatever you might call it. I share it because I know there are many churches who use this principle from Matthew 18 as a foundation for what amounts to secrecy and a lack of transparency. And frankly, as a well-studied reader of my Bible, I’d like to point out that that’s a gross misinterpretation of the text at best and, at worst, an intentional obfuscation and manipulation of the principles presented in this scripture.

I can’t pinpoint when or how I absorbed the idea that Matthew 18 supported shielding the wider church from truth. But as I’ve learned about the systems in place in many churches, it seems congruent. Silence and a lack of transparency provide essential cover for those whose behavior may not stand up to public scrutiny.

There is one last piece I’d like to point out. As I said, to the best of my knowledge, the decision to bar me from leadership was made unilaterally by the pastor in question. I’ve often wondered what he told the other staff members about what happened. Surely they noticed? But perhaps they, too, chose not to ask any questions.

Here’s the thing I think is worth considering: when my situation unfolded, was there anyone who could have challenged the decision that pastor made to remove me from leadership? I can’t answer that question, but I know that many churches – even those with large steering committees or leadership panels – have pastors who, when it comes down to it, still exercise almost absolute power. Remarkably, despite its obvious fragility, this leadership model seems to be fairly ensconced in many Evangelical spaces.

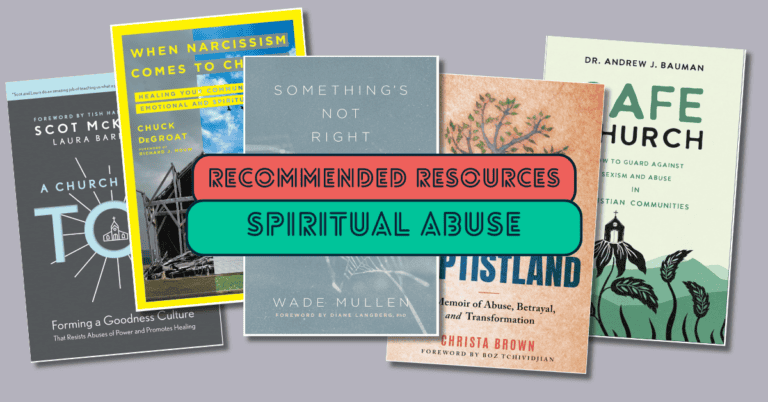

Some of these churches may have teams or committees that act as extensions or even enforcers on behalf of that central personality, but the people or groups in those roles don’t have effective ways to intervene or engage in issues involving that primary leader. In other words, if it goes against the desires (read: interests) of the person with that centralized control, people in those supporting roles may have tasks to execute, or be invited into discussions, but the primary leader’s voice or direction isn’t overridden, and his or her actions aren’t up for authentic review, accountability, or change at the behest of those others. (If you’ve experienced dynamics like this in your church or organization, I cannot recommend Chuck DeGroat’s When Narcissism Comes to Church more highly. It’s excellent.)

And look, I get it. Some people might say that’s as it should be. Nonetheless, the question worth considering is what happens when that powerful central personality gets it wrong?

For a time, I thought what my pastor had done was simply an error in judgment or maybe an overreaction. It was just a “mistake.” For what it’s worth, I don’t think he acted out of malice or any sort of intentional ill-will. I don’t think he’s a bad person; as Solzhenitsyn said, the line between good and evil runs down the middle of each of us. But, especially in his role as a pastor, his choices have powerful impacts on the people around him. His choices had an extremely detrimental impact on me and on my family for one.

I often tell my kids that “everyone makes mistakes.” But, as I also tell them, making a mistake does not dismiss you from responsibility for its consequences. When I screw up, I do what I can to engage with those I’ve affected and do the work of authentic repair. But, the first step in authentic repair is admitting that you’ve made a mistake, and that is just as true for figures in public roles as it is for anyone else. In my months of conversation with that pastor, I was the only person who ever admitted to any sort of “mistake.”

What I’ve learned in the past few years is that there are many churches out there where stories like mine are far from unique. And, likewise, the people with the power in those spaces are often unwilling to acknowledge any kind of error or misstep; instead, they seem to prefer to position themselves as trod upon victim servants, worn out by the burdens of their position. (Again, Wade Mullen’s short article, “Discrediting the Truth-Tellers” directly addresses this dynamic.)

"Yes; everyone deserves grace. But no one deserves a pass on repetitive and harmful patterns of behavior."

For any human, making a misstep is a bummer, and failure to take ownership of that mistake compounds the hurt experienced by those involved. But to make the same types of mistakes again and again and again is something else entirely. Yes; everyone deserves grace. But no one deserves a pass on repetitive and harmful patterns of behavior. And when we find ourselves in spaces where those patterns aren’t being stopped, it’s our responsibility to face that reality honestly. Most organizations have some sort of mission statement or stated goal, and those can be easy to rally behind. But I think the best way to identify the priority of any organization is to look at what it actually does – again and again and again.

In unhealthy church spaces, it can be difficult to find accessible paths for correcting what’s gone wrong. Even if people see that the actions of those in power are problematic or concerning, they often struggle to find meaningful ways to do anything about it. Sometimes, this is because of structures within the governance of the church or because of their own internalized submission to the unspoken requests that have been made of them. Those requests might be for silence, a willingness to look the other way when complaints, concerns, and problems arise, or for unconditional support of a person’s actions.

Other times, people entangled in these systems feel a strong obligation to actively defend or protect the system itself, regardless of what the tradeoffs may be. When friends feel compelled to betray the trust of those to whom they’ve promised to be a confidential space for open sharing, or lash out aggressively to chastise or pressure those who express disappointment or dissatisfaction with the system, I think the nature of that dynamic deserves careful examination.

I’ve already written that I chose, at the time of our departure, to insulate the church and the pastor from any potential criticism or judgement by keeping the full story of what had happened quiet. Fresh off the heels of being betrayed by a close friend who prioritized a sense of unwavering “unity” over the integrity of trust and honesty in our relationship, I had good reason to doubt the reliability of even my closest friends. Isn’t that sad? Isn’t it terribly terribly sad that I feared that, should I share openly and honestly with my Christian friends, I might be judged or rejected or worse?

Ironically, that did happen later when I shared a minute sliver of this larger story within a small group of close friends that I still, at that time, was in relationship with. Unfortunately, those friendships suffered greatly as a result of my sharing… and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the pattern I experienced in my relationship with my pastor was replicated in relationships with my friends from that church.

"…a community in which the silence of a suffering individual is preferable to collective discomfort or even disruption cannot be whole, healthy, or Christlike."

Sharing what was branded as gossip (a characterization which, again, I ardently protest) led to exclusion and dissolution of long-standing trust and relationship. I think that’s a shame. My own opinion is that a community in which the silence of a suffering individual is preferable to collective discomfort or even disruption cannot be whole, healthy, or Christlike. The message I received – both implicitly, and eventually, quite explicitly – was that my desire to speak openly about my own hurt and the experiences in which I was struggling was a threat to the church itself, and, based on what happened, it seems that perceived threat was, for some, quite intolerable.

I have to wonder, what precisely are the merits of a community that can only exist peacefully when no one challenges it out loud? What is the benefit of a leadership model that refuses to engage with unlovely human truth in a transparent and open way? In that system’s dealings with me, the priority was placed on what was called unity. But “unity” at the cost of authenticity is just assimilation.

For me, pretending to embrace relationship-building while dispensing with unclouded honesty is a soul-crushing charade, and not one I’m willing to participate in. To my eyes, a community that will not sacrifice its own comfort – and even stability – for the well-being and care of its people, looks nothing like a church trying to imitate a self-sacrificing Christ.

Over the last five years, I’ve had quite a few people pop back up from my old church community… reaching out via text or email or Facebook message, often after years… and they want to talk. Most of the time, they’ve left that church after some painful experiences, and for whatever reason, they decide that I’m someone they’d like to talk with. Those unexpected points of contact are the origins of this project.

As I said, I’m not there anymore, but looking in from the outside, informed by the stories I’ve heard from a surprising number of unexpected exiles, it appears that as people are being hurt, many others are completely unaware. That’s a big part of what motivated me to find a way for us to share our stories and experiences. To sit in the darkness of silence is suffocating and lonely.

Any one of these stories is important enough to stand completely on its own as a critique of what’s been done, of those who’ve actively participated in its doing, and of the passivity of a community that has often, en masse, seen fit not to ask too many questions or look behind the curtain. But as these stories are shared together, it’s the patterns and the repeated tactics and themes that may matter the most.

"…when any organization continues to prioritize protecting itself over its integrity, the wounded left behind the steamroller aren’t a malfunction or a misfire of the system; they’re a requisite feature."

I honestly don’t know how many of the more-than-a-dozen people who were initially invited to share in this project will contribute their stories. But whatever that number becomes over time, I hope seeing us all sharing side-by-side helps to communicate something I personally believe: when any organization continues to prioritize protecting itself over its integrity, the wounded left behind the steamroller aren’t a malfunction or a misfire of the system; they’re a requisite feature.

Many of us who’ve shared here have endured deep pain, profound loss, destabilization of our life’s rhythms, and damage to key elements in the framework of our faith. I hope that people who are currently a part of that specific church community will read all of these stories and absorb what’s being shared and expressed – often by people they have known as friends. I hope they’ll contemplate what they read and ask themselves hard questions. But no matter who you are, these stories matter. I believe strongly that bringing the truth into the light is not only holy work, but healing work. So here we are, hellbent on truth and justice and mercy for all.

The events I inadvertently kicked off during my conversation with a friend all those years ago were accidental. I certainly didn’t knowingly rock the boat. I never would have dared at the time.

But things are different now. I’m different now.

Now, I give my loyalty and my fidelity to my neighbors and to my friends. That is the way of Christ. I look at the fruit shown in the painful stories of those who’ve left our former church, and I think it stinks. And burns. I certainly left feeling more than a little scorched. My first loyalty is owed to Christ, and that means bringing the truth into the light, siding actively and wholeheartedly with those who are pushed out of their communities, and trusting that Jesus, as he disrupted systems and angered people with power, is an example worth trying to emulate in whatever way I can.

Thank you for taking the time to read my words and those of the others represented here. I am praying, as we put them out into the world, for the Kingdom to be done in, through, and by each and every one of us – you, me, and all the rest. Be well. Grace and peace to you all.